Cerebral hemorrhage

| Cerebral haemorrhage | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

Intracerebral haemorrhage |

|

| ICD-10 | I61., P10.1 |

| ICD-9 | 431 |

| MeSH | D002543 |

A cerebral haemorrhage (or intracerebral haemorrhage, ICH), is a subtype of intracranial haemorrhage that occurs within the brain tissue itself. Intracerebral haemorrhage can be caused by brain trauma, or it can occur spontaneously in hemorrhagic stroke. Non-traumatic intracerebral haemorrhage is a spontaneous bleeding into the brain tissue.[1]

A cerebral haemorrhage is an intra-axial haemorrhage; that is, it occurs within the brain tissue rather than outside of it. The other category of intracranial hemorrhage is extra-axial haemorrhage, such as epidural, subdural, and subarachnoid hematomas, which all occur within the skull but outside of the brain tissue. There are two main kinds of intra-axial haemorrhages: intraparenchymal haemorrhage and intraventricular haemorrhages. As with other types of haemorrhages within the skull, intraparenchymal bleeds are a serious medical emergency because they can increase intracranial pressure, which if left untreated can lead to coma and death. The mortality rate for intraparenchymal bleeds is over 40%.[2]

Contents |

Signs and symptoms

Patients with intraparenchymal bleeds have symptoms that correspond to the functions controlled by the area of the brain that is damaged by the bleed.[3] Other symptoms include those that indicate a rise in intracranial pressure due to a large mass putting pressure on the brain.[3] Intracerebral haemorrhages are often misdiagnosed as Subarachnoid haemorrhages due to the similarity in symptoms and signs.

Causes

Intracerebral bleeds are the second most common cause of stroke, accounting for 30–60% of hospital admissions for stroke.[1] High blood pressure raises the risk of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage by two to six times.[1] More common in adults than in children, intraparenchymal bleeds due to trauma are usually due to penetrating head trauma, but can also be due to depressed skull fractures, some may experience intense headaches. They may also go in to a coma before the bleed is noticed. A hit to the head or fracture to the skull may also cause this bleed. acceleration-deceleration trauma,[4][5][6] rupture of an aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation (AVM), and bleeding within a tumor. A very small proportion is due to cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.

Risk factors

Risk factors for BCH include:[7]

- Hypertension

- Diabetes

- Menopause

- Current cigarette smoking

- Alcoholic drinks (≥2/day)

Diagnosis

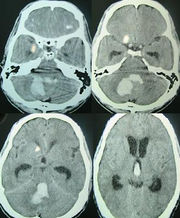

Intraparenchymal haemorrhage can be recognized on CT scans because blood appears brighter than other tissue and is separated from the inner table of the skull by brain tissue. The tissue surrounding a bleed is often less dense than the rest of the brain due to edema, and therefore shows up darker on the CT scan.

Treatment

Treatment depends substantially of the type of ICH. Rapid CT scan and other diagnostic measures are used to determine proper treatment, which may include both medication and surgery.

Medication

- Giving Factor VIIa within 4 hours limits the bleeding and formation of a hematoma. However, it also increases the risk of thromboembolism.[8]

- Antihypertensives are given to stabilize the mean arterial pressure at below 130 mmHg, but without causing excessive hypotension.[8]

- Mannitol is effective in acutely reducing raised intracranial pressure.

- Acetaminophen may be needed to avoid hyperthermia, and to relieve headache.[8]

- Frozen plasma, vitamin K, protamine, or platelet transfusions are given in case of a coagulopathy.[8]

- Fosphenytoin or other anticonvulsant is given in case of seizures or lobar haemorrhage.[8]

- Antacids are given to prevent gastric ulcers, a condition somehow linked with ICH.[8]

- Corticosteroids, in concert with antihypertensives, reduces swelling.[9]

Surgery

Surgery is required if the hematoma is greater than 3 cm, if there is a structural vascular lesion or lobar haemorrhage in a young patient.[8]

- A catheter may be passed into the brain vasculature to close off or dilate blood vessels, avoiding invasive surgical procedures.[10]

- Aspiration by stereotactic surgery or endoscopic drainage may be used in basal ganglia hemorrhages, although successful reports are limited.[8]

Other treatment

- Tracheal intubation is indicated in patients with decreased level of consciousness or other risk of airway obstruction.[8]

- IV fluids are given to maintain fluid balance, using normotonic rather than hypotonic fluids.[8]

Prognosis

The risk of death from an intraparenchymal bleed in traumatic brain injury is especially high when the injury occurs in the brain stem.[2] Intraparenchymal bleeds within the medulla oblongata are almost always fatal, because they cause damage to cranial nerve X, the vagus nerve, which plays an important role in blood circulation and breathing.[4] This kind of hemorrhage can also occur in the cortex or subcortical areas, usually in the frontal or temporal lobes when due to head injury, and sometimes in the cerebellum.[4][11]

For spontaneous ICH seen on CT scan, the death rate (mortality) is 34–50% by 30 days after the insult,[1] and half of the deaths occur in the first 2 days.[12]

The inflammatory response triggered by stroke has been viewed as harmful, focusing on the influx and migration of blood-borne leukocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages. New area of interest are the MC's [13].

Epidemiology

It accounts for 20% of all cases of cerebrovascular disease in the US, behind cerebral thrombosis (40%) and cerebral embolism (30%).[14]

It is two or more times more prevalent in black patients.[15]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Yadav YR, Mukerji G, Shenoy R, Basoor A, Jain G, Nelson A (2007). "Endoscopic management of hypertensive intraventricular haemorrhage with obstructive hydrocephalus". BMC Neurol 7: 1. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-7-1. PMID 17204141. PMC 1780056. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2377/7/1.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Sanders MJ and McKenna K. 2001. Mosby’s Paramedic Textbook, 2nd revised Ed. Chapter 22, "Head and Facial Trauma." Mosby.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Vinas FC and Pilitsis J. 2006. "Penetrating Head Trauma." Emedicine.com.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 McCaffrey P. 2001. "The Neuroscience on the Web Series: CMSD 336 Neuropathologies of Language and Cognition." California State University, Chico. Retrieved on June 19, 2007.

- ↑ Orlando Regional Healthcare, Education and Development. 2004. "Overview of Adult Traumatic Brain Injuries." Retrieved on 2008-01-16.

- ↑ Shepherd S. 2004. "Head Trauma." Emedicine.com. Retrieved on June 19, 2007.

- ↑ Major Risk Factors for Intracerebral Hamorrhage in the Young Are Modifiable Edward Feldmann, MD; Joseph P. Broderick, MD; Walter N. Kernan, MD; Catherine M. Viscoli, PhD; Lawrence M. Brass, MD; Thomas Brott, MD; Lewis B. Morgenstern, MD; Janet Lee Wilterdink, MD Ralph I. Horwitz, MD. Published in Stroke. 2005;36:1881.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 8.9 eMedicine Specialties > Neurology > Neurological Emergencies > Intracranial Haemorrhage: Treatment & Medication. By David S Liebeskind, MD. Updated: Aug 7, 2006

- ↑ MedlinePlus - Intracerebral haemorrhage Update Date: 7/14/2006. Updated by: J.A. Lee, M.D.

- ↑ Cedars-Sinai Health System - Cerebral Hemorrhages Retrieved on 02/25/2009

- ↑ Graham DI and Gennareli TA. Chapter 5, "Pathology of Brain Damage After Head Injury" Cooper P and Golfinos G. 2000. Head Injury, 4th Ed. Morgan Hill, New York.

- ↑ Guidelines for the Management of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage in Adults

- ↑ [1] Lindsberg e.a.: Mast cells as early responders in the regulation of acute blood–brain barrier changes after cerebral ischemia and hemorrhage

- ↑ Page 117 in: Henry S. Schutta; Lechtenberg, Richard (1998). Neurology practice guidelines. New York: M. Dekker. ISBN 0-8247-0104-6.

- ↑ Copenhaver BR, Hsia AW, Merino JG, et al. (October 2008). "Racial differences in microbleed prevalence in primary intracerebral haemorrhage". Neurology 71 (15): 1176–82. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000327524.16575.ca. PMID 18838665.

External links

- Parent friendly information on IVH in premature babies from The Hospital for Sick Children

- LPCH on Intraventricular

- Information on brain haemorrhage from Headway - the brain injury association UK based charity providing information and support

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||